This deck of cards refers to the events surrounding the crash of an American bomber in a Sheffield Park. They are also a meditation on the site today and the way in which the events of 50 years ago live on in the collective memory. I cannot now visit the site and see it as just a piece of woodland. The knowledge of what happened there is inextricably linked with the way in which I perceive the site. The imagery on the cards comes both from history and the contemporary, from the crash and the surrounding area. Walking through the park today many natural and man-made items are found. The aluminium ringpull from drinks cans is perhaps the commonest man-made object found and this contemporary twisted metal became for me a sort of metaphor for the twisted metal which would have been present 50 years ago. The ringpull is a recurring theme in the cards. The Eight of Clubs

shows examples found in Endcliffe

Park, while other cards, for example the Eight of Spades

show a stereotyped version. I speculated that maybe the

metal from the plane, through various stages of recycling

had once more come to be among the trees in Endcliffe Wood

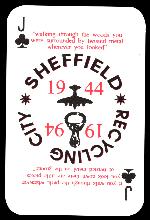

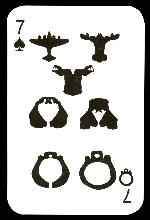

and this notion is referred to on the Jack of Clubs and

Seven of Spades.

shows examples found in Endcliffe

Park, while other cards, for example the Eight of Spades

show a stereotyped version. I speculated that maybe the

metal from the plane, through various stages of recycling

had once more come to be among the trees in Endcliffe Wood

and this notion is referred to on the Jack of Clubs and

Seven of Spades.

The idea of transformation and

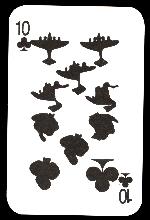

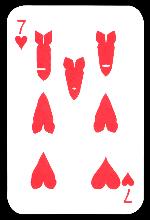

metamorphosis also appears in the Ten of Clubs, Seven of

Hearts, Eight of Hearts and the Jokers.

The idea of transformation and

metamorphosis also appears in the Ten of Clubs, Seven of

Hearts, Eight of Hearts and the Jokers.

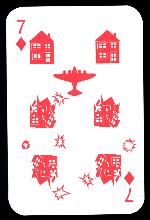

Whilst metal

ringpulls are the commonest man-made object in the park,

leaves are the commonest natural object and feature in

various forms in a number of the cards. The neighbourhood

of the crash, then as now, is a residential area. The

stylised 'safe' suburban house image is a reminder that the

plane narrowly avoided these houses. The bombed version of

this archetypal house is a reminder that the actual purpose

of the bomber was destroy property. In contrast to the

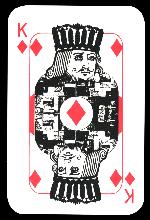

pictographic representation of the houses, actual

photographs or parts of photographs feature on the King of

Diamonds and Queen of Hearts

Whilst metal

ringpulls are the commonest man-made object in the park,

leaves are the commonest natural object and feature in

various forms in a number of the cards. The neighbourhood

of the crash, then as now, is a residential area. The

stylised 'safe' suburban house image is a reminder that the

plane narrowly avoided these houses. The bombed version of

this archetypal house is a reminder that the actual purpose

of the bomber was destroy property. In contrast to the

pictographic representation of the houses, actual

photographs or parts of photographs feature on the King of

Diamonds and Queen of Hearts

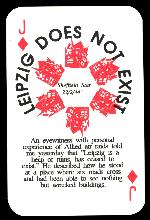

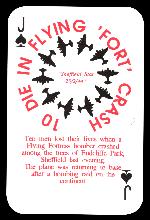

. Contemporary

newspaper stories are quoted on the Jack of Diamonds and

the Jack of Spades

. Contemporary

newspaper stories are quoted on the Jack of Diamonds and

the Jack of Spades

. The pilot was posthumously awarded

the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Jack of Hearts

carries an extract from his citation.

. The pilot was posthumously awarded

the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Jack of Hearts

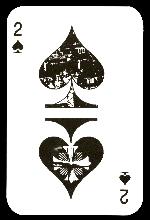

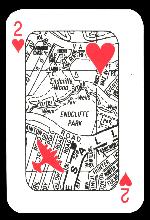

carries an extract from his citation. The Two of Spades shows the rooftops over

which the plane flew and the medal that the pilot received

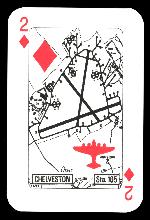

for avoiding them. The Two of Diamonds and the Two of

Hearts show maps of the start and finish respectively of

the crews' last mission.

The Two of Spades shows the rooftops over

which the plane flew and the medal that the pilot received

for avoiding them. The Two of Diamonds and the Two of

Hearts show maps of the start and finish respectively of

the crews' last mission.

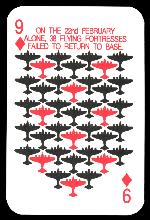

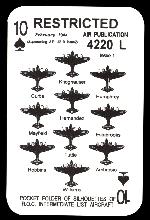

On that same day 38 Flying Fortresses

were lost, this is recorded on the Nine of Diamonds. Each

plane had a crew of ten, the names of the crew of the Mi

Amigo are shown on the Ten of Spades, which takes the form

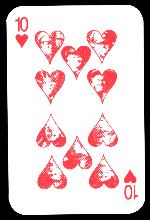

of a Royal Observer Corp. silhouette chart. The Ten of

Hearts includes tiny photographs of the ten airmen.

On that same day 38 Flying Fortresses

were lost, this is recorded on the Nine of Diamonds. Each

plane had a crew of ten, the names of the crew of the Mi

Amigo are shown on the Ten of Spades, which takes the form

of a Royal Observer Corp. silhouette chart. The Ten of

Hearts includes tiny photographs of the ten airmen.

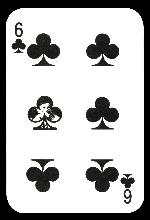

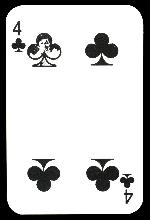

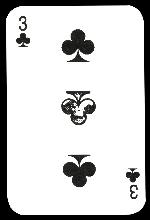

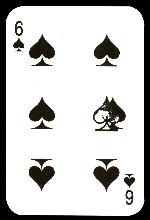

Single photos

of the crew also appear on the Six of Clubs, Four of Clubs,

Three of Clubs, Six of Spades, Four of Spades and Six of

Diamonds.

Single photos

of the crew also appear on the Six of Clubs, Four of Clubs,

Three of Clubs, Six of Spades, Four of Spades and Six of

Diamonds.

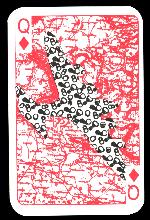

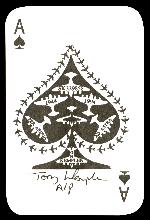

Maps play a vital role in any journey but in

a bombing campaign can also take on the function of death

warrant to those on the ground in the target area. I also

find maps interesting for their aesthetic appeal. The Queen

of Spades and the Queen of Diamonds include maps of

Sheffield and Germany respectively. The map reference for

the crash site, SK329858 was the title of a body of work

shown at the Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield at the time of

the 50th anniversary. This map reference appears on the Ten

of Diamonds and the Ace of Spades. Aerial photography was

an important part of a bombing campaign. Automatic cameras

were mounted on the aeroplanes in order to record the

results of the bombardment. The images on the Ace of Clubs

and the Queen of Spades could be such photographs.

Maps play a vital role in any journey but in

a bombing campaign can also take on the function of death

warrant to those on the ground in the target area. I also

find maps interesting for their aesthetic appeal. The Queen

of Spades and the Queen of Diamonds include maps of

Sheffield and Germany respectively. The map reference for

the crash site, SK329858 was the title of a body of work

shown at the Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield at the time of

the 50th anniversary. This map reference appears on the Ten

of Diamonds and the Ace of Spades. Aerial photography was

an important part of a bombing campaign. Automatic cameras

were mounted on the aeroplanes in order to record the

results of the bombardment. The images on the Ace of Clubs

and the Queen of Spades could be such photographs.

Unlike a

conventional pack of cards in which the backs are all

identical, this pack can be arranged into six groups of

nine cards which each form a simple jigsaw pattern

recalling the overall theme of the pack. The list of names

is based on the real names of the crew but becomes

increasingly distorted, an echo of the way in which

memories may become distorted with time. Finally the peanut

on the Nine of Hearts refers to the crews' mascot, a small

dog of that name.

Unlike a

conventional pack of cards in which the backs are all

identical, this pack can be arranged into six groups of

nine cards which each form a simple jigsaw pattern

recalling the overall theme of the pack. The list of names

is based on the real names of the crew but becomes

increasingly distorted, an echo of the way in which

memories may become distorted with time. Finally the peanut

on the Nine of Hearts refers to the crews' mascot, a small

dog of that name.